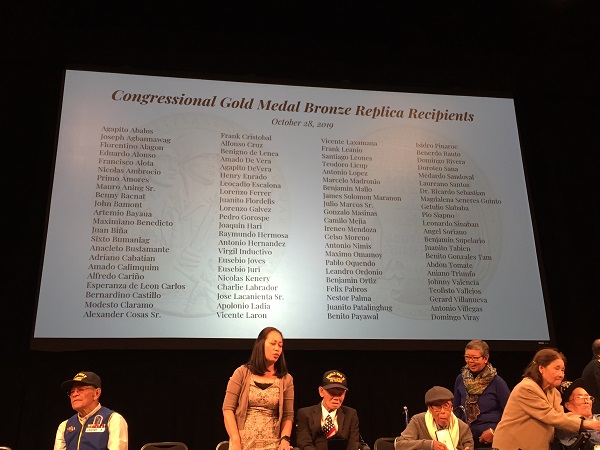

On Monday, October 28, 2019, my sister Heidi and I attended the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony at the Herbst Theatre in San Francisco to receive a bronze replica of the medal on behalf of our father, Henry Empleo Enrado. This event is the 21st such ceremony in the state of California since the October 25, 2017, Congressional Gold Medal ceremony in Washington, DC. Among the 87 Filipino veterans honored on this day, seven were able to attend and rightfully took center stage. In 1946, Congress passed the Rescission Acts, which revoked veterans benefits and payments to the Filipino soldiers, and denied them their U.S. citizenship, which had been promised to them in exchange for their service. Individuals and nonprofit organizations worked tirelessly for decades to get these veterans recognized. It took 71 years, and many of the veterans had passed, but what a moment for those who are still alive to see justice prevail. Maraming Salamat to the Filipino Veterans Recognition and Education Project, the Bayanihan Equity Center, and their partners and supporters who pushed for Public Law 114-265.

The Bayanihan Equity Center, formerly known as the Veterans Equity Center, and the Filipino Veterans Recognition and Education Project were the event sponsors. Founded in 1999, the Bayanihan Equity Center’s original intent was to serve Filipino Veterans of WWII and their families. In 2018, the center changed its name to reflect the expanded mission and services provided to older adults and adults with disabilities in San Francisco. The Filipino Veterans Recognition and Education Project (FilVetREP), a nonpartisan, community-based, all-volunteer national initiative, was founded with the mission to “raise awareness through academic research and public information, and to obtain national recognition of Filipino and Filipino-American WWII Soldiers in the United States and the Philippines for their wartime service to the U.S. and the Philippines from July 1941 to December 1946.”

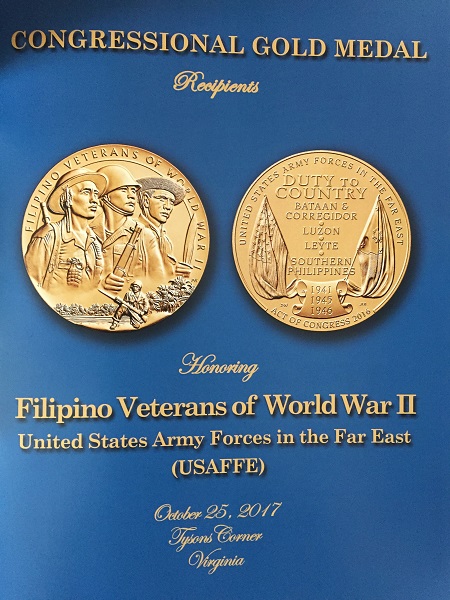

The Congressional Gold Medal Design

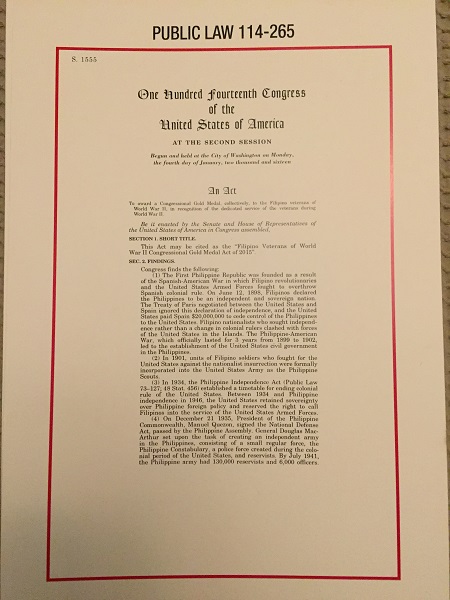

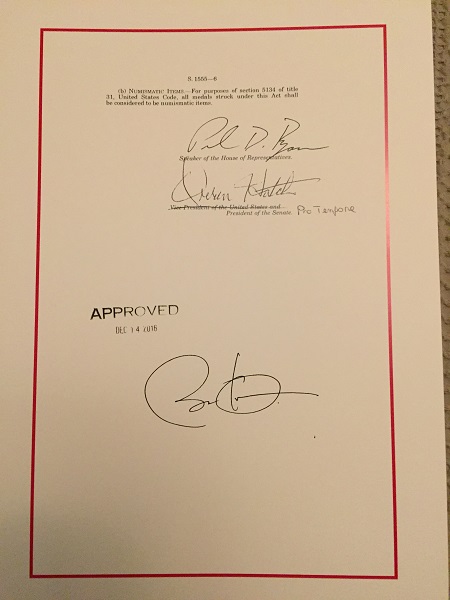

Here’s a brief history of the Congressional Gold Medal’s design, taken from the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony program from the October 25, 2017, event: “In accordance with Public Law 114-265 (signed by President Barack Obama on December 14, 2016), the Filipino Veterans of WWII Congressional Gold Medal Act of 2015 awards a Congressional Gold Medal (CGM) collectively to the Filipino Veterans of WWII in recognition of their outstanding wartime achievements and honorable service to the U.S. during WWII.

“By law, the Secretary of the

Treasury and the U.S. Mint are tasked by the U.S. Congress with the design,

minting and circulation of the CGMs. In this case, the U.S. Mint designed and

struck a CGM specifically to honor and commemorate the Filipino, American, and

Filipino American Veterans of WWII for whom the medal is awarded. The medal is

distinguishable in appearance and portrays the historical significance and

accomplishments of the veterans. CGMs are also considered “non-portable,”

meaning they aren’t meant to be worn on the uniform or other clothing. The

Filipino Veterans of WWII CGM is one of a kind – an original and true symbol of

honor, valor, integrity and selfless service to our Nation.”

The Filipino Veterans Recognition and Education Project, led by Major General Tony Taguba, U.S. Army Retired, worked closely with the U.S. Mint Project Team. Also involved were the Project’s academic advisory team, living WWII veterans, and the U.S. Mint’s design team. Of the original 43 medal designs of the front and back, the group selected four designs of the front and one design of the back. FilVetREP reviewed the selected designs to ensure that specific criteria was met, namely, that the design, inscriptions, and design elements, such as the uniform, insignias, weapons, etc., were historically accurate. The final designs of the CGM were approved by the Secretary of the Treasury on August 25, 2017, and produced by the U.S. Mint.

The front, or obverse, depicts the faces of soldiers and guerrillas in their period uniforms, headgear, and weapons who represent the Philippine Commonwealth Army, Philippine Scouts, First Filipino Infantry Regiment, Second Filipino Infantry Battalion, 1st Reconnaissance Battalion, and Recognized Guerrillas – unites that comprised major combat forces of the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) from July 26, 1941 to December 31, 1946. The bottom of the obverse features a U.S. Army soldier in a “guard and defend position” on a beachhead in Leyte during the liberation of the Philippines, then a Commonwealth or territory of the U.S., on October 20, 1944.

The back, or reverse, of the

CGM highlights the theme “Duty to Country” – “the core value inherent in

citizenship, patriotism, courage, honor, selfless service, integrity of men and

women who willingly served their country in defense of freedom and liberty. The

thousands of soldiers who fought and died in battle in the Philippines over a

four-year period did so with uncommon valor and intrepidity. The four major

campaigns inscribed on the reverse – Bataan and Corregidor, Luzon, Leyte, and

Southern Philippines – were fought in an archipelago of more than 7,000 islands

that exemplified the herculean mission of U.S. troops defending a key nation in

the war in the Pacific. The dates emblazoned on the scroll below the campaign –

1941, Japanese attack of the Philippines; 1945, liberation of the Philippines

and the defeat of the Japanese Imperial Forces; and 1946, the end of war and

passage of the Rescission Acts by Congress, which revoked veterans benefits and

payments to the Filipino soldiers, and denied them of their U.S. citizenship –

evoke the period of desperation, humiliation, and daunting experience of the

Filipino Veterans of WWII on their wartime service.”

Former Speaker of the House

Paul Ryan formally presented the CGMs to the Veterans at Emancipation Hall,

Capitol Hill, Washington, DC, on October 25, 2017. The original medal is on

display at the Smithsonian Institution. FilVetRep hopes to develop an education

program to complement the CGM and “educate the American public on the history

and worthiness of sacrifice made by the Veterans in earning their recognition

with the medal.”

“The interminable cost of their mission and brutal ordeal to defend the U.S. and the Philippines were unprecedented. They had guaranteed their mission with their lives and in full measure to defend and save their country against a formidable and inhumane enemy. For 75 years, the WWII Veterans remained proud, steadfast, and loyal to the U.S. despite the injustice, discrimination, and sense of inferiority they suffered after the war. They had waited all these long years and envisioned the day the U.S. and Congress would finally recognize them for their war-time accomplishments. They will not be forgotten, but will be remembered eternally.”

Back to the San Francisco ceremony

I received the bronze replica of the CGM from Major General Eldon P. Regua, U.S. Army (retired). It was a really moving ceremony and moment when I received the medal. We missed having our sister Joyce attend with us, but Heidi is already planning on sending an application to recognize our father’s younger brother, Delano Enrado, who also served during WWII in the Philippines.

After the ceremony, Heidi and I celebrated by having lunch at Max’s Diner at the Opera Plaza, a few blocks up from Herbst Theater. A handful of family members from the event were also dining there. Heidi noticed one of the veterans from the stage and went up to him and congratulated him. It turned out that Aniano Triunfo was the oldest living veteran at the event – at 101 years young! And he was in possession of his wits, literally. When Heidi bent down to shake his hand and congratulate him, he asked her, “Is this lunch free?” One of his daughters who had overheard him told Heidi to say yes. We both laughed at his attention to cost because this is something our own father would have said, no doubt as a result of having lived through the Great Depression.

The moment made me both miss my father and feel very proud for his service and for his sacrifices. Our father fought in the battle of Leyte, a three-month battle and one of the bloodiest in the Pacific Theater. It was not without its cost. I didn’t realize that his nervousness and paranoia were the result of post-traumatic stress disorder until after his death, when his cousins told us at the luncheon following his funeral that “Henry was not like that before the war.” For our family, the Congressional Medal of Honor recognizes the great sacrifices he made to protect our freedom.

[…] on the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony honoring the Filipino veterans of WWII. You can read it here. Below is a photograph from the […]